Hartford, Conn. : Taylor & Huntington, No. 2 State St., [between 1863 and 1880]

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication.

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011649196/

Republic of Suffering

The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust is an extraordinary book that provides a look back in time to see how 19th-century Americans viewed death. She also describes how the Civil War fueled the growth of the funeral industry and the creation of national cemeteries, and caused the military to expand its functions dramatically. This book shows the sheer gruesomeness of the war in ways that books focusing on the battles never could.

In modern times, we try to fight off death, to slow down death, to focus on living and life. In the Civil War era, a more Victorian philosophy still existed–that it was important to die a “good death.” That meant that you were at peace with yourself, with others, and with God. When a soldier died, fellow soldiers and officers tried to comfort the family by assuring them that their loved one had died such a death. Some soldiers carried with them letters to send to family members in case of their demise, and these letters tried to provide the same reassurance.

Growth of Embalming

Officers who died in the line of duty were often embalmed so that they could be returned home to be buried with family, rather than in mass graves and/or on the battlefield where they died–a fate suffered, all too often, by the common foot soldier. With the number of deaths of officers occurring, more and more embalmers were needed, causing the mourning process of loved ones to increasingly need facilitation, thus leading to the growth of the funeral industry.

Anonymity of Civil War Deaths

One of the most horrifying aspects of this book concerned soldiers who died and were buried where they fell, without markers identifying who they were and without the families being notified. Before the Civil War began, the military had no official formal way to identify or count the dead or to notify the next of kin. Casualty lists were not perfect, either. As the war dragged on, people involved in the war developed methods to try to prevent their fellow soldiers from being buried without identification or acknowledgment, but it still happened all too frequently. It wasn’t unusual for families to wander around battlefields after the shooting stopped, to look for the bodies of their parents and children, to take them back home for burial.

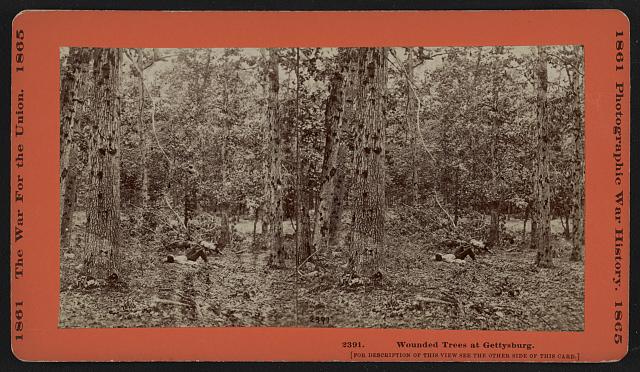

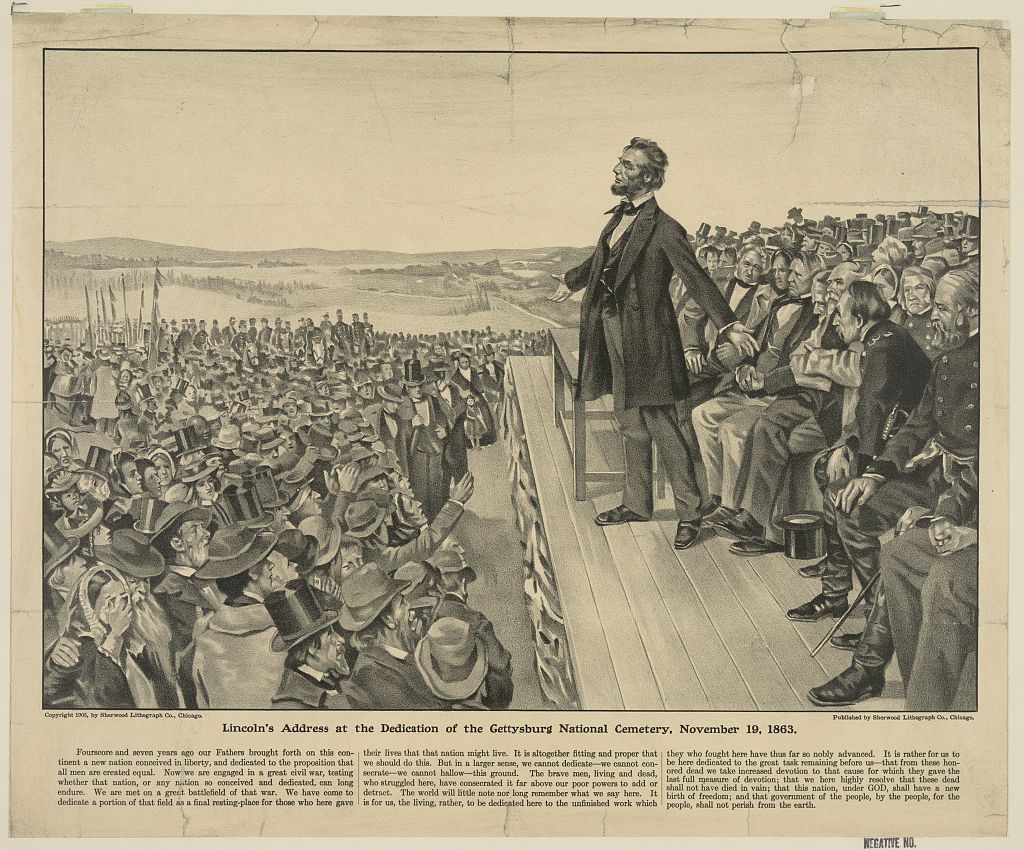

National Cemeteries

During the war years, the federal government began establishing and using national cemeteries and, after the war, made a concerted effort to retrieve the bodies of Union soldiers buried in southern battlefields; to identify them; and to rebury them in the north. By the end of the war, the number of national cemeteries increased from zero in 1861–to 74. An astonishing 303,536 Union bodies were retrieved and reburied at a staggering cost of $4 million. The government wasn’t as effective with the identification portion of the process, with the identity of 50% of the bodies remaining unknown. Unfortunately for the black soldiers who survived the war, the labor and horror involved in reburying the dead often fell on them.

Spirituality of the Era

It comes as no surprise that a rise in spirituality and occult practices occurred in this era. The Republic of Suffering discusses that in some detail; another amazing book that focuses on mysticism in the United States is called Occult America: The Secret History of How Mysticism Shaped Our Nation and was written by Mitch Horowitz.