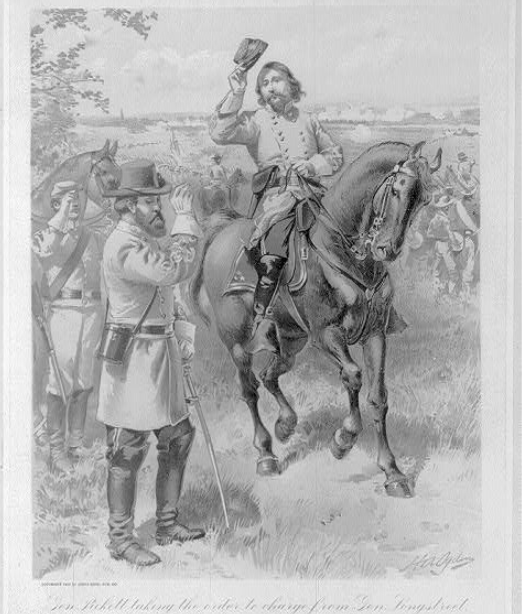

By the time the smoke cleared and combatants left the field after Longstreet’s Assault on July 3, 1863—popularly known as Pickett’s Charge—the carnage was horrific. All told during three bloody days in July, the Union Army saw an estimated 23,049 casualties: 3,155 killed, 14,529 wounded, and 5,365 missing/captured.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, 1,500 Union soldiers were wounded or killed during the assault alone—and among them was twenty-one-year-old Captain Wells Waite Miller. Despite the severity of his wounds, unlike many of his comrades in battle, Wells survived. While there’s no way to definitively know why he did when so many previously strong and healthy men did not, he did have one significant advantage that I’ll explore later in this post.

Pickett’s Charge: Retrieving Men From the Field

When the Pickett’s Charge assault ended, the Union was, understandably enough, “battered and worn down.” So, it must have been difficult to get the wounded and bleeding men the help they needed. It’s hard not to wonder how many of them might have survived had they not bled out or suffered too much from thirst. Water in the area quickly became contaminated, too, adding to the challenges.

Once the men were retrieved from the war-torn field, surgeons in Gettysburg “began the paralyzing task of sorting the dead and dying from those whose lives might be saved.” To that end, the Union Army set up about one hundred field hospitals in homes, barns, schools, churches, the courthouse, and shops to provide medical attention to those still living.

Estimates of wounded needing care in Gettysburg: 14,000 Union soldiers and 6,000 Confederates left behind. The Army of the Potomac kept about one hundred surgeons in the area to care for them, and some contract surgeons filled in gaps—but surely not enough to properly care for 20,000 wounded soldiers.

Gettysburg civilians pitched in to help despite their own struggles, post-battle, with memories of that tragic time including how “rapid death was in many ways more merciful than waiting for infection or pneumonia to slowly take its toll.” Despite everyone’s best efforts, it’s unlikely that the men got as much time and attention as they needed given the huge number of casualties.

Around July 8, five days after Pickett’s Charge, the military began construction of a general hospital for the wounded soldiers: Camp Letterman. It opened around July 21 and around thirty women served as nurses, including some Gettysburg civilians. By this time, though, Wells had been in Ohio for at least ten days.

Once it became practical, doctors also transferred the wounded to general hospitals in nearby towns, but the final field hospital still in operation in Gettysburg—Camp Letterman—was open through October. According to the American Battlefield Trust, the last of the wounded left this small farming town in January 1864 along with the last of the medical personnel.

Disease and Civil War Soldiers

Many men undoubtedly died directly from their wounds. Overall, though, two thirds of Civil War soldiers who perished died not from wounds but from disease. As PBS notes, “Crowded conditions, poor hygiene, absence of sanitary disposal of garbage and human waste, inadequate diets, and no specific disease treatments was a formula for disaster . . . There was no understanding of bacteria as a cause of disease or insect-borne infections.”

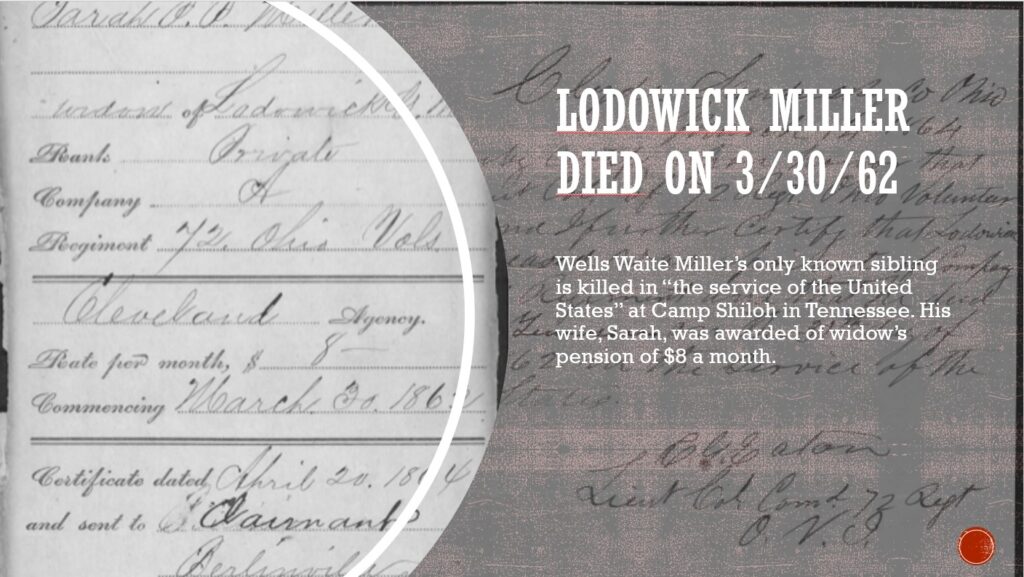

The brother of Wells Waite Miller, Lodowick, had already died of typhoid in Shiloh shortly before that battle began. Typhoid was the second most common cause of death by disease during the war, also referred to as “camp fever.”

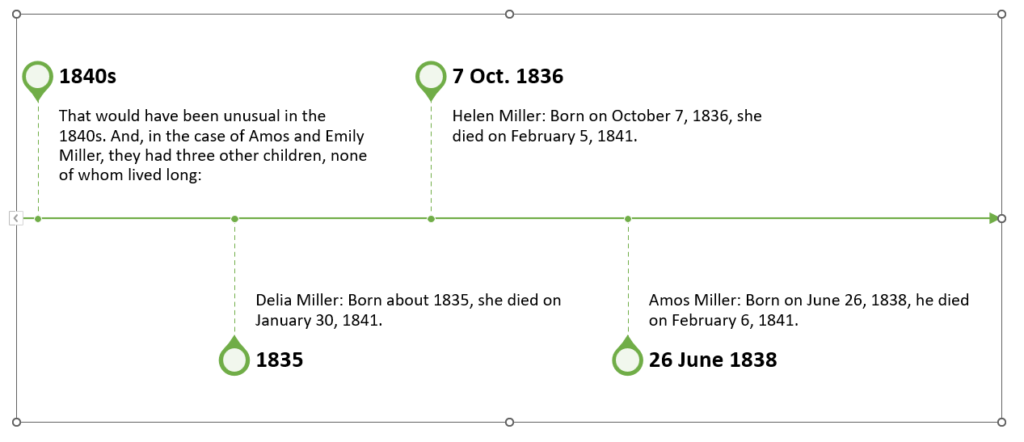

It’s likely that the three young siblings of Wells and Lodowick who died within a week of one another twenty-some years earlier also died of a contagious disease.

As far as Wells, after being severely wounded at Pickett’s Charge, it wouldn’t have been unusual for him to also contract and die from disease.

What was different for him? Why did he live for forty-three more years?

Post-Pickett’s Charge: Wells Waite Miller’s Journey

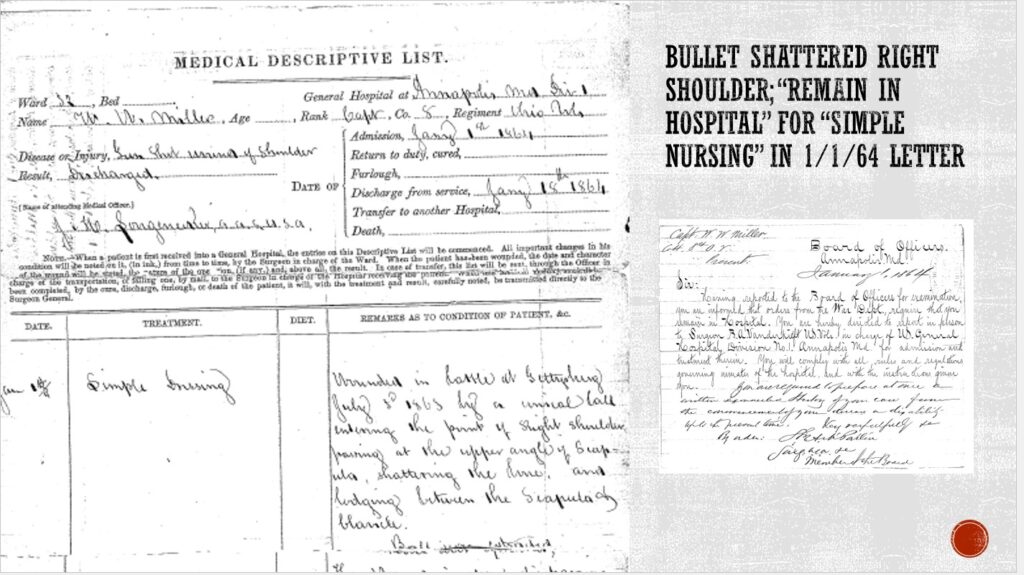

Although he fought through most of the battle of Gettysburg, during the afternoon of day three on July 3, a bullet hit and lodged along his scapula on his right shoulder, shattering the bone. While on the ground, expecting to be trampled to death by Confederate horses, his hearing was damaged by all of the cannon fire and other noises along with his eyesight.

What, specifically, happened to Wells during the first several days after the battle, I don’t know. But, by July 11, he was already home with the Cleveland Daily Leader publishing the following: “We are without any of the details which Captain Miller could doubtless give. He was suffering quite severely from the effects of his wound, but we trust, now he is at home, he will speedily recover.”

So, unlike many to most of the Union wounded at Gettysburg—who received care from exhausted and overworked doctors, nurses, and civilians and would be surrounded by the sick and given contaminated water—Wells got the personal attention of his loved ones. It’s likely that the resources of Calvin Caswell, a prominent citizen in Castalia and Wells’ future father-in-law, allowed Wells to travel home on a train to receive the best care available at that time away from crowded conditions that were breeding grounds for disease.

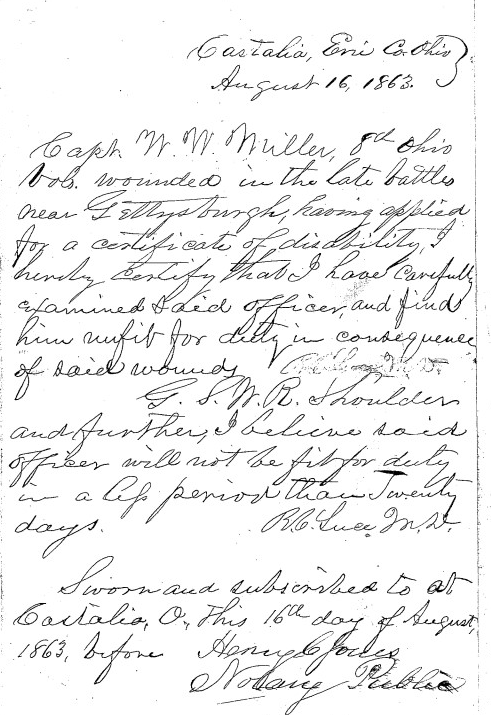

Wells then applied for and received sick leave and was ultimately considered “unfit for duty.”

When he reported to the General Hospital in Annapolis, Maryland on January 1, 1864, the medical report recommended that he “remain in hospital” for “simple nursing.”

Just seven days later, he was honorably discharged because he could not return to active military service. This apparently frustrated him—but may have saved his life just as receiving medical care in Ohio, away from the horrors of the battlefield, may have done so in July 1863.

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller (current post)

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.