When Wells Waite Miller (b. February 20, 1842) was a child and teenager, “the debate over slavery raged in the nation’s political institutions and its public places.”

Because this post is part of an ongoing blog series about the life and times of a forgotten Civil War hero—Wells Waite —I want to know what the Miller family thought about the slavery question. If they had any abolitionist leanings, did they put their beliefs into practice? Unfortunately, I haven’t found direct evidence one way or the other (which doesn’t mean that I won’t speculate). What is clear: the region in which they chose to settle in the 1850s (Castalia, Ohio, near Sandusky, located along Lake Erie) had its fair share of abolitionists—and the Millers arrived when Underground Railroad activity was heating up to its maximum.

Several years after Amos and Emily Miller moved from Enfield, New York to rural Castalia, they sent 16-year-old Wells to a town about forty miles away—Oberlin, Ohio—known as a “hotbed of abolitionism” and, not much later, as the “town that started the Civil War” because of its anti-slavery advocacy and actions. The Millers sent him to further his education in this environment without their presence as they, naturally enough, would have remained on the farm—and it was too far for Wells to have regularly traveled back and forth by horseback.

During the three years that Wells attended the Preparatory Department at Oberlin College—1858, 1859, and 1860—this town was considered one of the most radical places to live in the entire nation. Even when two volatile national controversies erupted during Wells’ tenure in Oberlin (more about those later in this series), Amos and Emily did not withdraw him from the school to bring him home. From my perspective, it’s therefore likely that the Millers didn’t approve of slavery. What specific anti-slavery statements they made or actions they took, if any, may be lost in time or, preferably, yet to be discovered.

Oberlin College

“The school [Oberlin College] became a beacon for the nation’s most progressive students, and together with a thoroughly abolitionist faculty and community, they set about the mission of ridding America of its greatest and most pressing sin—slavery.” (Oberlin, Hotbed of Abolitionism: College, Community, and the Fight for Freedom and Equality in Antebellum America by Brent Morris)

Oberlin College was founded in 1833 on evangelical Christian principles, and this private school became exceptional when it began to admit people of both genders and all races. Its Preparatory Department was created to prepare students “beyond the elementary grades to undertake advanced work in other departments or colleges, to enter technical schools, or to begin working.”

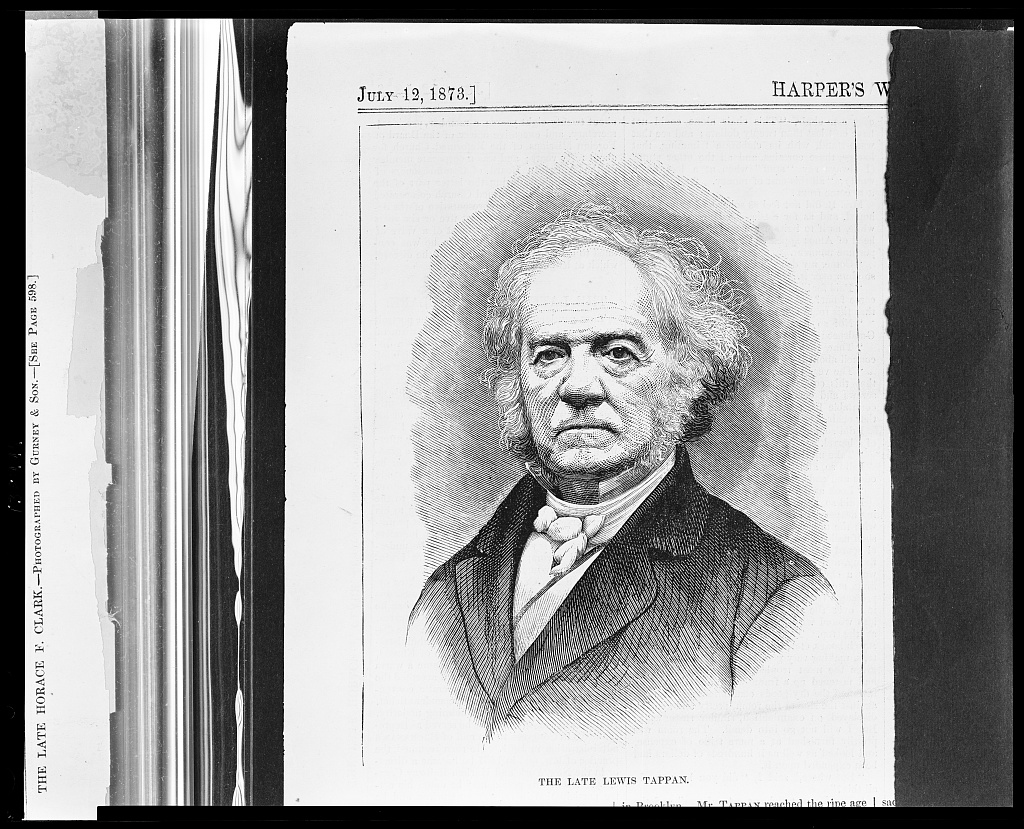

In 1833, brothers Arthur and Lewis Tappan—along with abolitionists Theodore Dwight Weld and William Lloyd Garrison—formed the American Anti-Slavery Society that demanded an immediate end to slavery along with equal rights for African Americans. The Tappan brothers provided financial support to Oberlin College with Lewis sending money to support the abolitionist newspaper, The Emancipator.

As a sign of how differently Oberlin College, then known as the Oberlin Collegiate Institute, operated in comparison to others, while many colleges of this era expelled students who advocated for abolitionism, Oberlin welcomed these outcasts. The Lane Theological Seminary students represent the most famous (or infamous, depending upon one’s point of view). After the students held a series of debates about the realities and morality of slavery in spring of 1834, the trustees of the Lane Theological Seminary, located in Cincinnati, Ohio, voted to abolish the newly formed anti-slavery society and censor all student gatherings.

About fifty students who became known as the Lane Rebels left the seminary along with a trustee and a professor from the school. One of the Tappan brothers and Reverend John Shipherd, a co-founder of Oberlin College, then invited them to Oberlin. The rebels listed conditions before they agreed, including that the college would not ban any student because of color and that they would respect students’ freedom of speech rights. College officials agreed by a narrow vote and, in 1835, Oberlin permitted students of all races to attend.

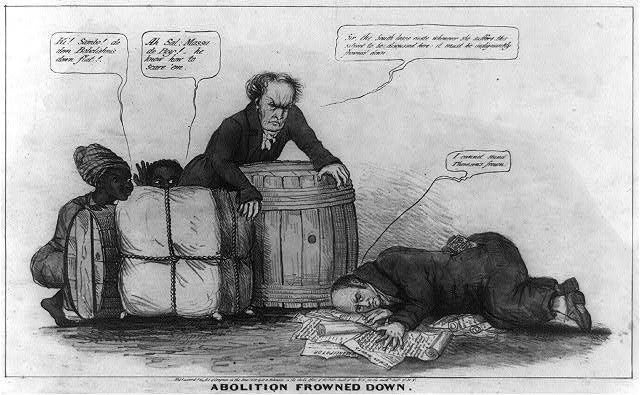

Great Maelstrom

One contemporary critic of the educational institution who was from southern Ohio, author Brett Morris, notes, called the college a “great maelstrom of seditious faction . . . exerting a more potent influence in exciting sectional animosities . . . than any, I may say all, the other malcontent institutions in the U.S.” Other legislators, according to Morris, called Oberlin a “thoroughfare for slaves en route to Canada” as well as a “banditti of lawbreakers” and “negro stealers supported by enemies of this country abroad, and emissaries at home.”

Beliefs expressed by many from the college were, in fact, considered so outrageous that, in 1842-1843, the state government of Ohio debated about whether they should revoke the Oberlin Collegiate Institute’s charter altogether. Despite the heated rhetoric, the charter was not revoked that year—or in the hotly contentious years yet to come. This may be, in part, because those most aggressively against the college were not specific enough in their charges against the institution.

Bringing it Back to the Millers

An entire library could be written about Oberlin’s role in abolitionism. For now, though, how likely is it that Amos and Emily Miller would have been comfortable with Wells living in Oberlin during this era if they were pro-slavery?

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism (current post)

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.