Birth of Aaron Miller, Jr.

Born on February 17, 1758, Aaron Miller, Jr. was just two years old when the French and Indian War began, which kept British forces in the Colonies busy fighting—and spending money on military-related expenses.

This war lasted until the Treaty of Paris in 1763 when France ceded its mainland North American territory to Britain. This war and subsequent treaty vastly increased the territory held under the British crown, but it was an expensive war, one that led to Britain increasing taxes on those living in the Colonies. Couple that with George III coming to the throne in England in 1760—and his support for a stricter rule of people living in the Colonies—and the foundation was being laid for what would become the American Revolutionary War.

American Revolutionary War

During modern school-aged lessons, this is when children would likely be told how Paul Revere—the Midnight Rider—shouted that the British were coming. In reality, stealth was crucial so shouting anything would have been counterproductive. Plus, Revere considered himself to be British and would have said that the “regulars”—or “Redcoats”—were coming.

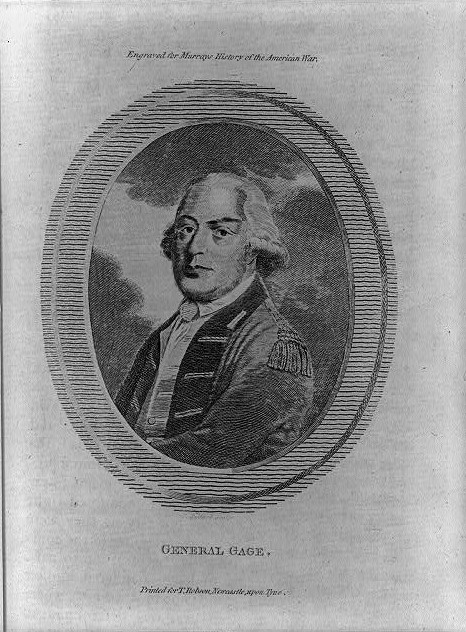

On April 19 in the town square of Lexington, about seventy Colonists known as Minutemen met up with the British forces and gunfire was exchanged. Afterwards, the British continued on to their geographic goal, Concord, where approximately four hundred Colonists were waiting for them. They clashed with the British soldiers and, after many years—even decades—of what was at best an uneasy relationship, these events triggered the Revolutionary War.

So, who were these men from the Colonies? Meaning, who exactly were the “Minutemen?”

Minutemen

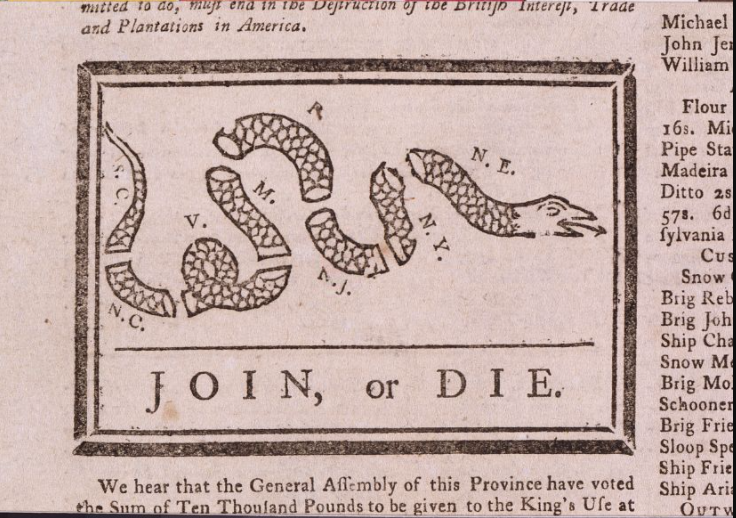

Shortly after arriving in the New World, British immigrants in New England would form militia groups whose job was to protect their settlements from any outside threats, and these units would stay relatively close to home. By the time that the Revolutionary War was imminent, six generations of men had already served in local militia groups.

Minutemen, meanwhile, were militia members who had been chosen by officers to serve as a “small hand-picked elite force which were required to be highly mobile and able to assemble quickly”—ideally at a minute’s notice. These men were those with the “enthusiasm, reliability, and physical strength” to serve in this select force, usually the top twenty-five percent of a militia unit. In general, these men were, at most, 25 years old and they served as the first responders of their day, a type of mobile special forces.

Minutemen had been training for action since the political protest known as the Boston Tea Party took place on December 16, 1773; so, by the time that violence erupted in Lexington and then Concord, this group of men, located throughout the Colonies, had already drilled for sixteen months to become battle ready. So, the natural response to the clashes with British Redcoats was to get the word out to Minutemen in other parts of the Colonies to increase their presence where needed.

Aaron Miller, Jr. Responds

On April 20, 1775, news of these skirmishes reached Colonel John Paterson in Lenox, Connecticut through a courier who’d ridden through the night to sound the alarm. In response, Colonel Paterson and his hand-picked Minutemen headed where the fighting had been taking place—and their number included Aaron Miller, Jr.

According to the United States Rosters of Revolutionary War Soldiers and Sailors, 1775-1783, Aaron enlisted as a private on April 29, 1775 in Captain David Noble’s company under Colonel Paterson. Although specifics of Aaron’s actions in 1775 are virtually non-existent and although sources show dates that vary slightly—we do know that he responded to a muster roll on August 1, 1775 and that an “order for bounty coat or its equivalent in money” was dated October 26, 1775—we can follow along in his footsteps through the actions of Colonel Patterson.

On May 26th, 1775, Colonel Paterson informed the Massachusetts Commonwealth’s Committee of Safety that he had 496 men in the field and, on June 15, this regiment’s status changed from Minutemen to soldiers in the Continental Army for a period of eight months. The Continental Army was created by Congress on June 14, 1775 and placed under the command of General George Washington, and the men were being trained to become—and then fought as—a regular army.

He reappeared as a private in Captain Enoch Noble’s company in Colonel John Brown’s regiment on June 29, 1777. Brown’s claim to fame, mostly forgotten, is that he was the one who accused Benedict Arnold of being a traitor.

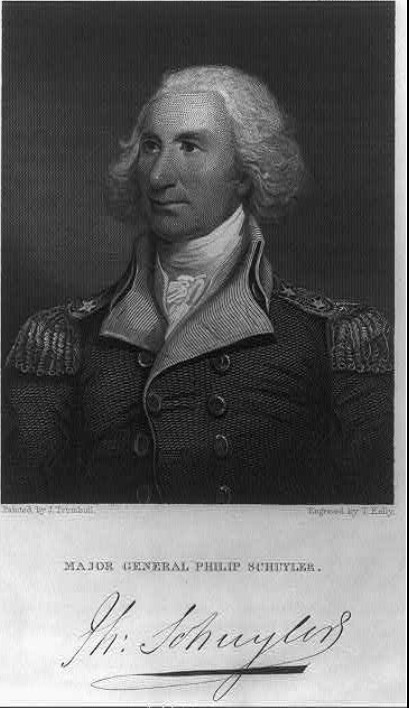

Twenty-four days later, Aaron was discharged “with Northern army; company ordered out by Gen. Fellows and Committee of Safety at request of Maj. Gen. Schuyler. Roll certified at Sheffield.” That same day, though, he was listed as a member of Captain John King’s company in Colonel Ashely’s (Ashley’s) Berkshire regiment. He served in that capacity for 25 days (July 21 to August 15, 1777) and was given mileage home with a limit given of 74 miles.

He fought at the Battle of Saratoga in Stillwater, New York, a crucial turning point for the Continental Army that took place in September and October 1777 and served as a decisive victory for the Colonists.

Aaron served as a private again in Captain Rufus Allen’s company of the militia of Maltross in Colonel David Rosetter’s regiment on October 14, 1780 for a three-day period when the group responded to an alarm. On October 18, he was re-enlisted for another three-day period to respond to an alarm. Because he never had nine consecutive months of service, he apparently was not awarded a pension for his military service.

Post-War Life of Aaron Miller

Although there are many gaps in our knowledge of Aaron’s military service and slight inconsistencies in the records, we do know that, after surviving the war, he married twenty-year-old Bethiah Dewey on June 19, 1783, just two and a half months before Britain signed the Treaty of Paris that officially recognized the United States as an independent country. The couple married at the First Church of Pittsfield, located in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and this fruitful couple had twelve children. A daughter named Clarissa was born first, on June 6, 1784; the baby of the family, Amos, was born on June 11, 1805.

One of their sons, Dewey, lived to be 100 years old. In an interview in the Batavian on October 22, 1877, he reminisced about his father serving as a soldier in the Revolutionary War. He notes how his father had fought in the battle at Stillwater and worked as a blacksmith, “with whom I worked, making hoes and other tools.” According to this article, Aaron moved to Remington, New York in about 1792 and, in 1800, to “Brookfield, Madison county.”

Aaron lived for 29 years beyond that move, dying on June 14, 1829 at the age of 71. His youngest child, Amos, would have five children of his own with his youngest named Wells Waite Miller. Perhaps stories of Aaron’s bravery and patriotism inspired Wells when the drumbeats of war pounded once more.

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War (current post)

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.