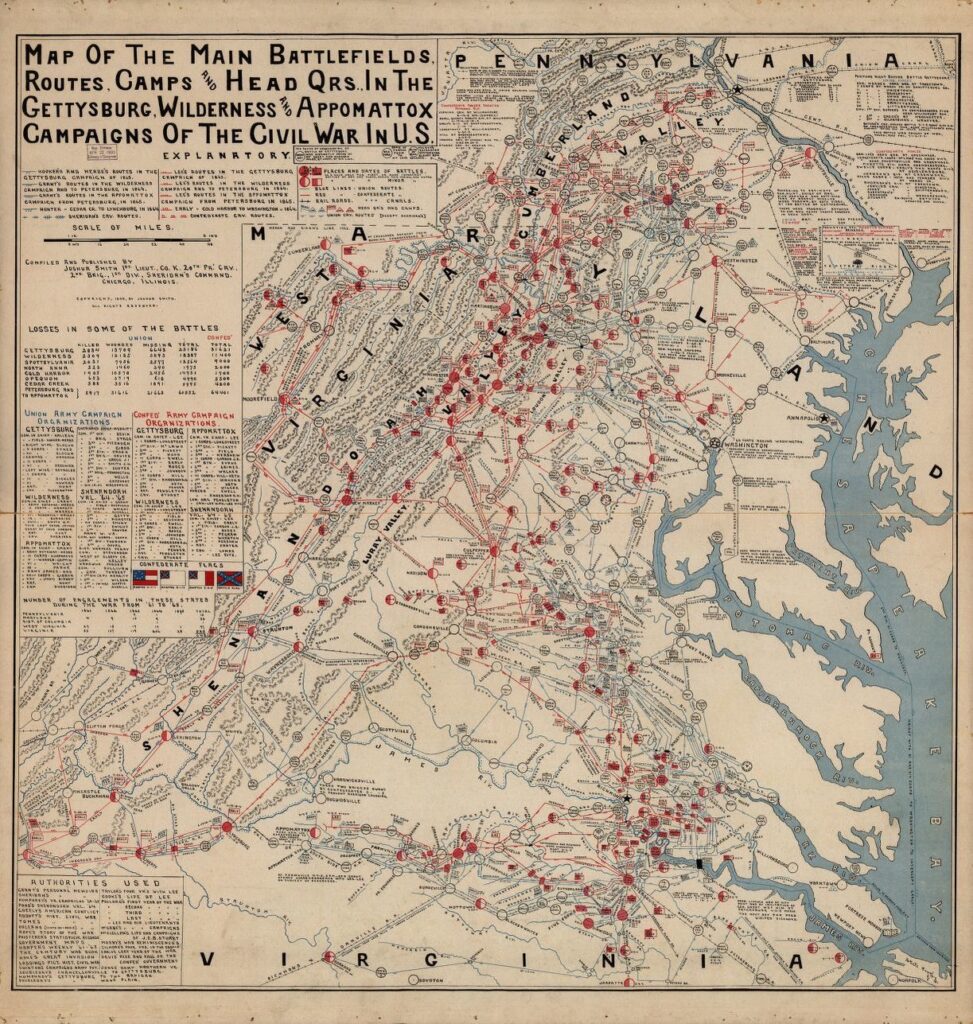

In 1999, my husband and I took our two young sons, aged nine and almost seven, to see the Gettysburg battlefield in Pennsylvania. We attended an orienting presentation of the Electric Map where small bulbs lit up to demonstrate where each of the two sides—Union/United States and Confederate—were located during key parts of the three-day battle. To give you a sense of that experience, here is a map of the Gettysburg campaign from the Library of Congress.

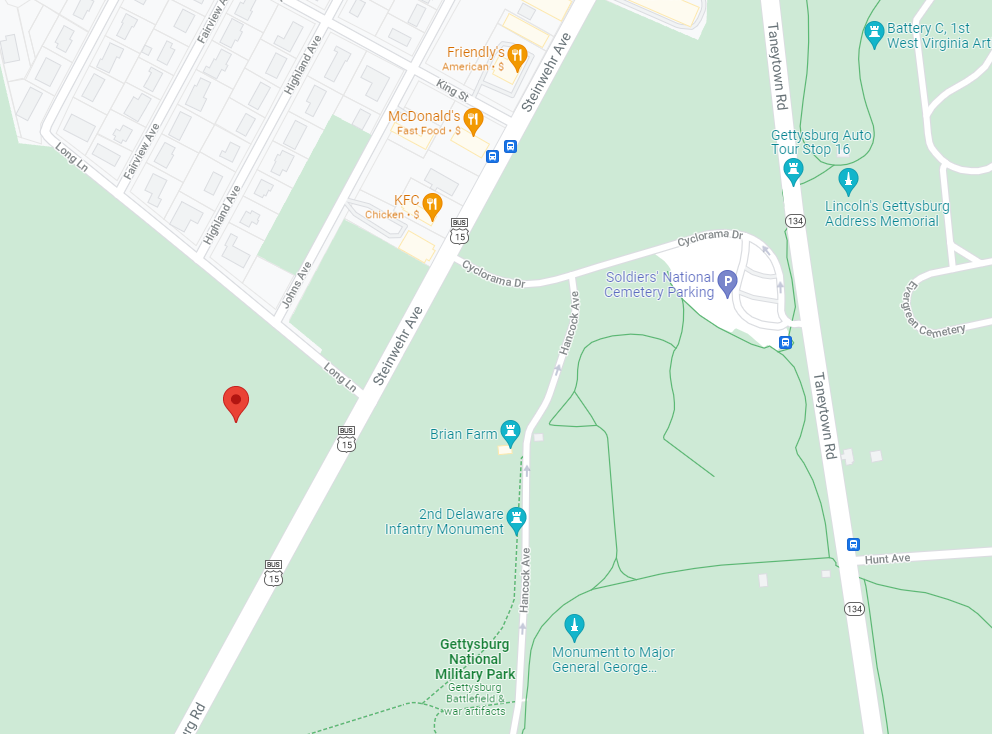

We visited the Gettysburg Cyclorama, an historic oil-on-canvas painting of battle scenes laid out in a 377-foot circle. And, of course, we trekked the battlefield itself, up Little Round Top—Big Round Top, too—through the rocks of Devil’s Den, along Plum Run, across the Wheatfield and Peach Orchard, and so much more. We went to ranger-led presentations, including fireside chats in the evenings; followed the detailed driving instructions of an auto tour recording; and stopped to examine countless battlefield monuments and the Eternal Peace Light Memorial.

Gettysburg Battlefield: We Return

In each of our next nine visits, we continued to expand the depth and breadth of our explorations—and every one of them included time spent learning more about what’s often called Pickett’s Charge. I felt chills when I stood on Seminary Ridge where Confederate soldiers who would become involved in Pickett’s Charge began their bloody one-mile march across open fields on July 3, 1863—and when I stood by the Copse of Trees on Cemetery Ridge where Union soldiers fought during that horrific charge.

It took until our eleventh visit, though, before I realized that small bands of Union soldiers who fought during Pickett’s Charge were detached from the main fighting units. This included about 180 men of the 8th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI).

On our twelfth visit, I learned that historians and scholars are now recognizing how pivotal a role the 8th OVI played at Pickett’s Charge and, therefore, the entire battle of Gettysburg—and this ultimately led to my desire to focus on one particular soldier: Captain Wells Waite Miller who almost died for his bravery.

Gettysburg: Pickett’s Charge

Picture the scene. According to Lt. Col. Franklin Sawyer, 8th Ohio, “I received an order . . . to move my regiment . . . to the front of our position . . . and to hold my line to the last man.” This was after a period of several hours where “everything seemed unusually quiet for a battle field.” In response to his orders, at 4 p.m. on July 2, Sawyer then sent Miller “across the Emmitsburg road with skirmishers, and at once advanced to his position.”

There, for the next 24 hours, the 8th OVI constantly fought in “murderous” skirmishes, ones in which 40 of their men died as shrieking shells exploded, dying men moaned, and no one could reasonably hope to retreat—only to fight and survive . . . or to fight until death.

How Did They Get to Gettysburg?

What comes next is a quick snapshot from when the Civil War officially began at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina on April 12, 1861 until when Wells Waite Miller was marching to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1863. More details will come in subsequent blog posts.

Although optimistic people on both sides of the War of the Rebellion predicted that only a short burst of fighting would be needed to decide its outcome, the conflict that became known as the Civil War dragged on for four long and bloody years. Overall (high level only, here!), as the war lengthened, the Union Army could supply its men more effectively than the Confederate Army could, which would give the Union Army an advantage. In modern lingo, the Confederacy was suffering from more supply chain issues.

Taking the fight to Pennsylvania would also allow Lee to move the military conflict away from his home state of Virginia, which had seen so much brutal fighting and whose citizens needed respite. If all went perfectly, Lee could perhaps force President Abraham Lincoln to legitimize the Confederacy as a separate nation, one in which they could maintain the institution of slavery.

By June 1863, Lee had accomplished his goal of marching on Union soil for a second time with 75,000 pairs of weary feet under his command. Meanwhile, on June 28, Lincoln—still looking for the right general to turn the war’s tide in favor of the Union—replaced Major General Joseph Hooker as the head of the Union’s Army of the Potomac with Major General George Gordon Meade.

Meade’s first duty? To coordinate the efforts to fight Lee in Pennsylvania.

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America (current post)

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.