Oscar Schultz Kriebel and His Connection to Wells Waite Miller

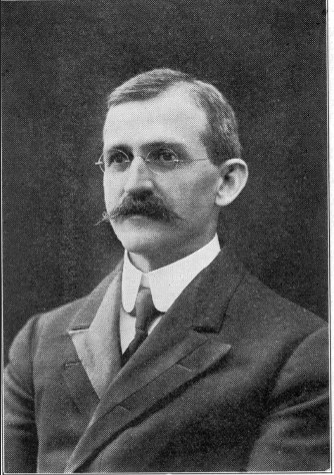

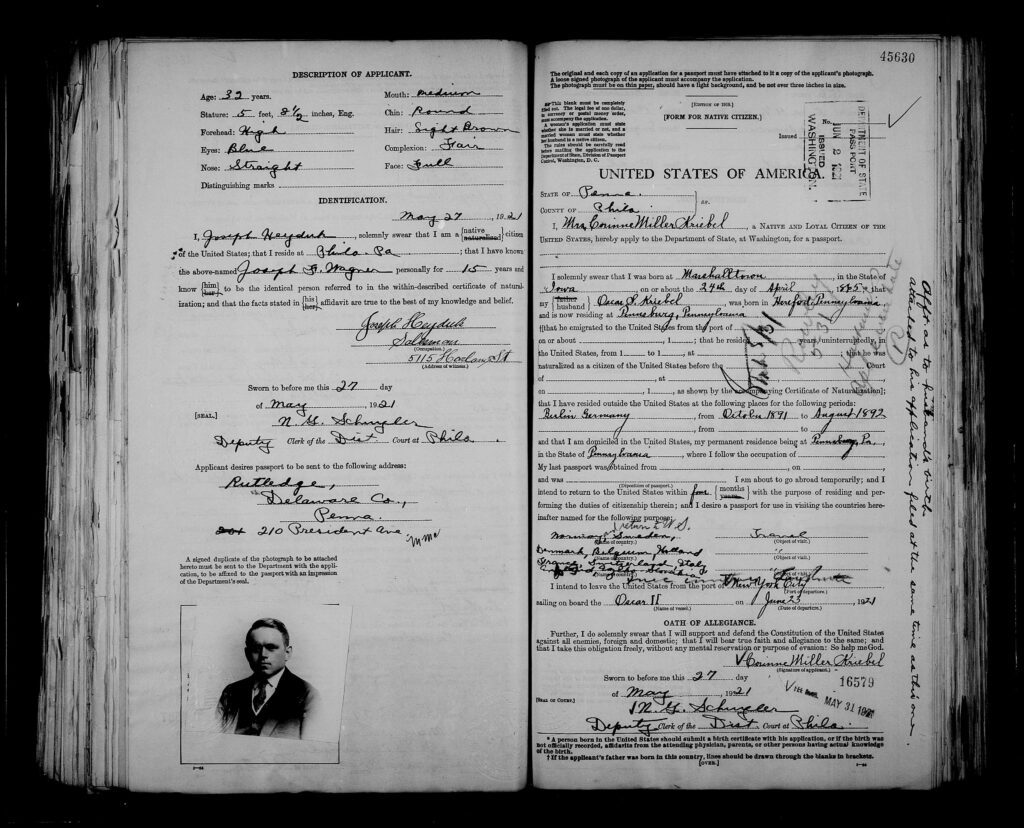

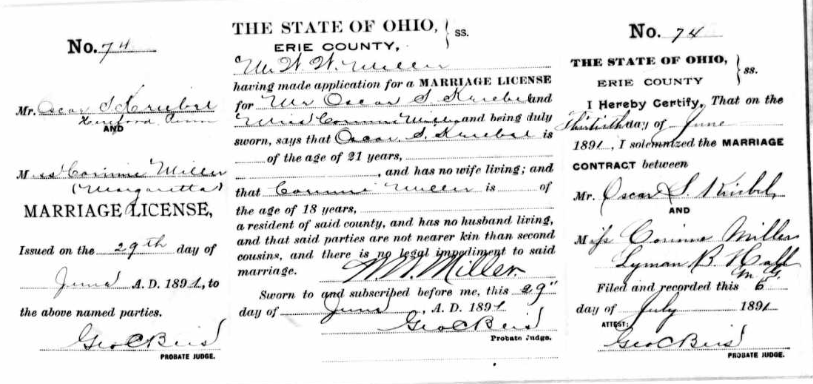

The photo of Oscar Schultz Kriebel shown above was used in his passport in 1921. Oscar became part of Wells Waite Miller’s life much earlier, though, perhaps as early as 1890. That year, Wells’s daughter, Corrine, was attending Oberlin College. Here’s a bit about her.

Corrine Miller was born on April 24, 1865 in Marshalltown, Iowa.

So, she was about twenty-five years old while living in a place where she met a fellow student named Oscar: the town of Oberlin, Ohio. When they met, he had two great passions in life: pursuing higher education and his Schwenkfelder faith. Oscar was quite devoted to this Christian denomination, one observed by only a small group of faithful followers in his lifetime. Today, there are only four Schwenkfelder churches in the world, all located in the area of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The video that follows provides a good overview of the faith’s founder and its history.

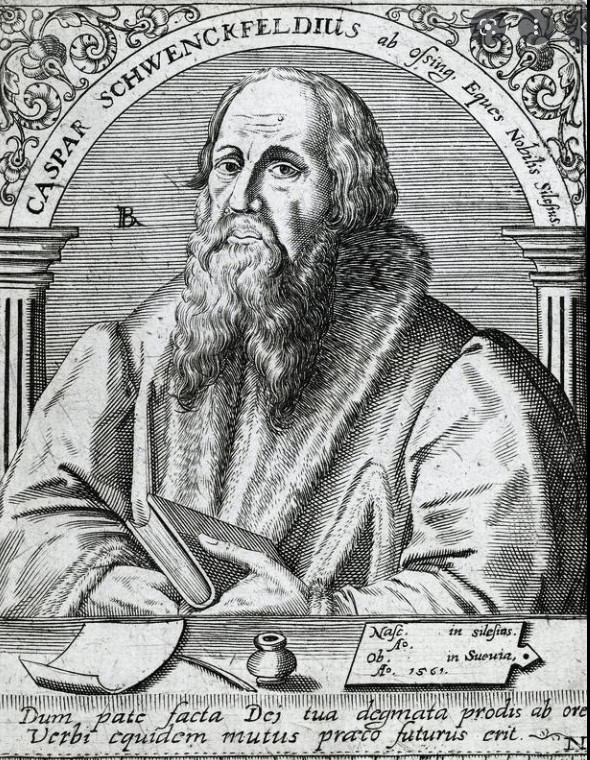

Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig

The name of this type of Christian faith was derived from the beliefs of a 16th century Protestant Reformation leader and Silesian nobleman named Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig. Silesia is located in Central Europe, largely in today’s Poland but with sections in the Czech Republic and Germany. (His name is spelled in a wide range of ways.)

He was born in either 1489 or 1490. In 1518 or 1519, Schwenckfeld became inspired by the viewpoints of Martin Luther—and then he took them even further, believing that “people could communicate directly with God, that true spirituality didn’t need all the machinery of hierarchies and priests and sacraments, that church was not a place but a community.” He was “dedicated to the mission of bringing into the life of the people a type of Christianity winnowed clean from the husks of superstition and tradition, and grounded in ethical and spiritual reality.”

In short, he wanted to create a “Middle Way” that would allow all Christians to worship together, avoiding excesses of Catholicism and Lutheranism. Luther, not surprisingly, didn’t agree with Schwenckfeld’s points of view (in fact, he considered him a simpleton) and Silesian authorities eventually exiled him. His entire body of work was banned at the Council of Trent; other banned works included those by Luther and John Calvin, so he was in good Reformation company.

People who continued to believe in Schwenckfeld’s ideas—they called themselves “Confessors of the Glory of Christ”—were labeled as heretics and often fined, imprisoned, persecuted, exiled, enslaved, or forced into military service. Women were placed into stocks; their children were removed from families and put into homes where they could be raised in the Catholic faith. Eventually these so-called heretics were even denied a plot in a church graveyard and couldn’t have friends and family present at their burials.

In 1726, more than 500 of them, understandably enough, fled to Saxony. By 1734, 208 Schwenckfelder followers in forty family groups (with only twenty-four different surnames) immigrated to the American Colonies, arriving on September 22. They braved violent ocean storms and other dangers before arriving safely and settling in the Philadelphia area near the Anabaptists and other religious groups considered to be fringe. A painting, created in 1934, shows their arrival: The Landing of the Schwenkfelders from the St. Andrew. In the picture I just linked to, here’s a thought: surely they looked more worn down and frazzled that the painting shows.

Susanna Dietrich Schultz and Christopher Kriebel

Among their numbers: Susanna Dietrich Schultz, Oscar’s widowed maternal ancestor, and his paternal ancestor, Christopher Kriebel. Oscar’s great-grandfather, John Schultz, became a popular Schwenkfelder minister in the United States and, although life may have been better in this country, one descendant of these immigrants called the subsequent era an “American period of privation and impoverishment.”

No other Schwenkfelder groups immigrated to the United States and no groups have existed anywhere else, globally, except in this southeastern Pennsylvania enclave since 1826 when the last European Schwenkfelder follower died. Those in the United States didn’t try to recruit people to their group, believing that this practice would go against Christian liberty, which meant that new members largely married or were born into the faith. Some of the immigrants moved away from the Pennsylvania settlement while others chose to affiliate with other religious groups, both of which further reduced their numbers.

Back to Oscar Schultz Kriebel

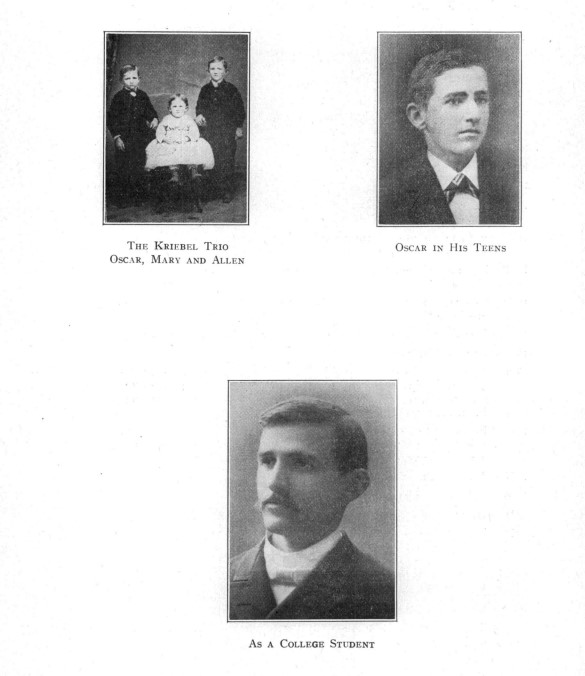

As for Oscar, he was born in Hereford, Pennsylvania on September 10, 1863, the second child of Andrew and Christina (née Schultz) Kriebel. Andrew died in 1876 when Oscar was only thirteen years old, and so he and his siblings—Allen, aged 15, and Mary, aged 10—needed to take on much of the responsibility on their farm. Oscar thereby “early learned the lessons of industry, frugality, patients and tireless toil,” according to the January 1936 issue of “The Perkiomen Region” when they published a memoriam of Oscar.

Because the Schwenkfelder community strongly believed in the value of education as a way to enlightenment and liberty, they began a public school system in 1765 for students of both genders, regardless of religious creed. So, although Oscar had plenty of chores on the farm, he also attended the village school where, at recess, he participated in debates and became known for having an exceptional ability to memorize.

His world would begin to open up even further, both as a solo traveler and with his wife Corrine (who, you might remember, is the daughter of Wells Waite Miller). More about all of that in another post!

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One (current post)

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.