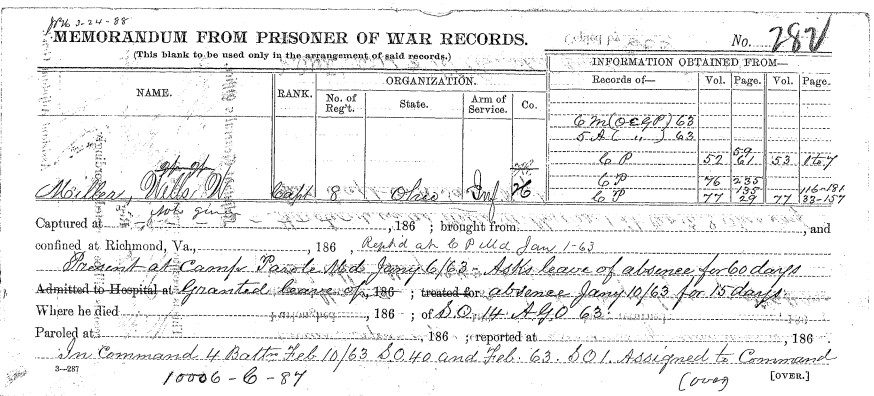

After the brutal fighting at Antietam on September 17, 1862, Wells Waite Miller of the 8th OVI headed to Harpers Ferry, Virginia with his unit where they went to rest, reinforce, and resupply. On October 29, 1862, they began a nineteen-day march to Falmouth, Virginia where they set up a winter camp on the north side of the Rappahannock River. Wells Waite Miller, however, was not with them. That’s because, about a year and a half after Wells enlisted—and about seven months after his only remaining brother’s death at Shiloh, and a month and a half after the bloody battle at Antietam—he was captured by Confederate forces. The date of his capture, according to Wells, was November 6, 1862. Fortunately, this was before the truly brutal prisoner of war camps existed and, instead, he was sent to a camp to await a prisoner exchange.

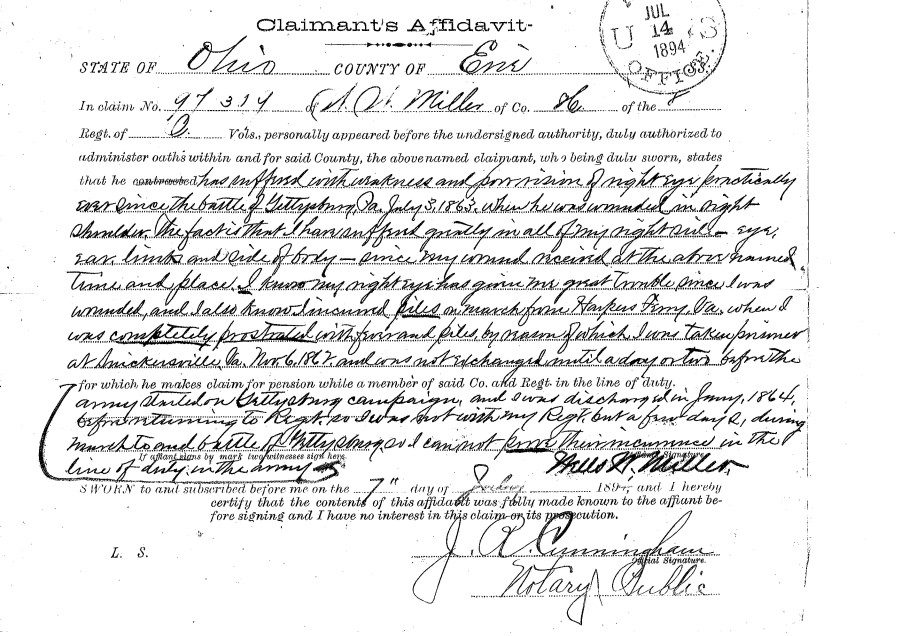

What likely made Wells more vulnerable to capture was not glamorous. A couple of days after his unit skirmished at Snicker’s Gap, VA, after significant amounts of marching, he began to suffer from “piles.”

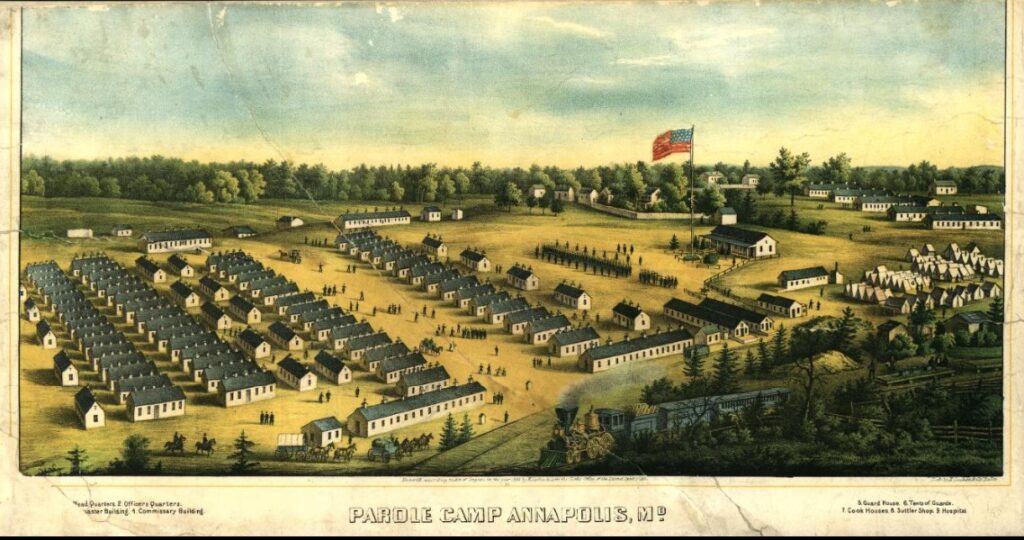

In other words, hemorrhoids—and this painful condition apparently slowed him down. After being captured, Wells was taken to Camp Parole in Annapolis, Maryland where he was listed as a prisoner of war on November 12. This town was located 85 miles northeast of where his unit planned to hunker down for the winter. So close—and yet so very far away.

More About Camp Parole

Much of what I’ve pieced together about this story has come from either A Low, Dirty Place: The Parole Camps of Annapolis, MD 1862-1865 by R. Rebecca Morris or from National Archive records about Wells Waite Miller. The YouTube video below features the author.

At this point of the war, both sides were still trying to figure out how to handle all of the prisoners they’d captured. Initially, no need was seen for prisons or prisoner exchange systems because both sides believed that the war would be short lived (with, of course, their side winning). On July 11, 1861, though, the United States army took nearly 1,000 Confederates as prisoners and needed to figure out what, exactly, to do with them.

Army officials decided that those prisoners should swear an oath of allegiance to the United States, promising that they would no longer take up arms. They were then paroled. This system had worked well enough in the War of 1812 with men signing the oath being taken at their word. These men would then go home or rejoin their units, theoretically as non-combatants.

So, just a month later, in Missouri, three Civil War privates on each side were exchanged for one another; but, in general, the prisoner problem only continued to grow without a practical agreed-upon solution. After all, once captured, enemy soldiers needed food and shelter and, often, medical care. Soldiers needed to be taken from their units to guard these prisoners, reducing the fighting forces, with prisoners being captured in previously unimaginable numbers.

Congress passed the first prisoner exchange legislation in December 1861 but it took until July 22, 1862—not that long before Wells was captured—that a somewhat workable system existed. In general, one U.S. private would be exchanged for a Confederate one. This was a weighted system, though, so—because he was a captain—six privates would need to be released in exchange for Wells. This would make it more challenging for him to secure his release.

Insights About Camp Parole

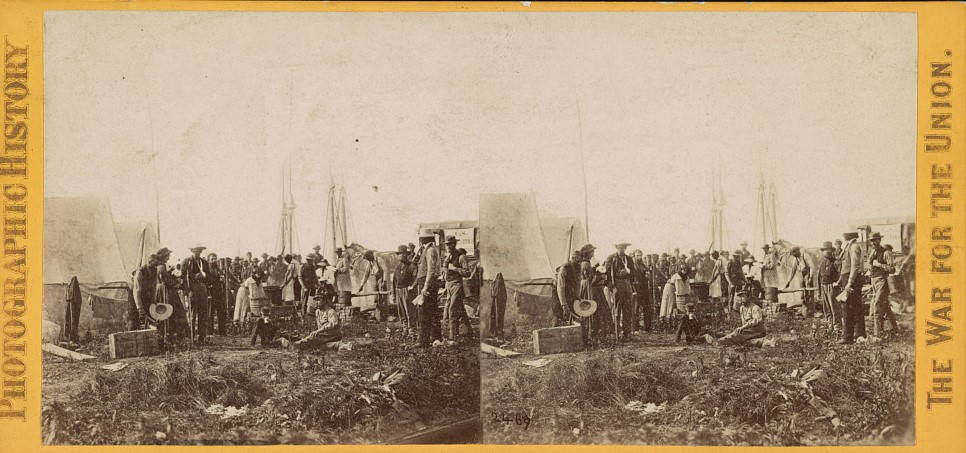

When soldiers first arrived at Camp Parole, they were required to bathe. “Their clothes and shoes were thrown into College Creek, where, as long as 30 years after the end of the war, those sturdy leather boots were still to be exhumed from the mud of that stream.”

A Christian Commission volunteer who served at Camp Parole later remembered how there were side-by-side rows of barracks there: about 100 to 150 feet long and at least twenty feet wide. Sometimes, groups of soldiers occupied a single large room while, other times, fifteen-foot rooms were formed through the use of boards as partitions. Beds filled the barracks used as a hospital, and one of them served as a chapel where religious services were held. Hastily constructed, the quality was poor. “The ceiling, walls, and floor, were so loosely constructed that in almost any place, that one might thrust his flat hand through the cracks.”

Camp Parole quickly overflowed with prisoners and, ultimately, three different locations existed although exact locations are not known. Tents were apparently used to house the overage; at one point, a U.S. soldier climbed into the State House dome and shared how he saw a “sea of white tents spreading in every direction . . . home to thousands of soldiers captured by the Confederates and returned to the Union army.”

This, then, is where Wells Waite Miller resided for a few months. He had requested a 60-day furlough in January to visit home and, on January 10, he was awarded a fifteen day leave—only a fourth of what he’d requested but surely quite welcome.

![]()

Although no exchange date is listed in his military records, after his release, he returned to the 8th OVI. Just a day or two after his return, Wells shares in his affidavit, he began to march with them to a small town in Pennsylvania, which would have been on June 26. The name of the town? Gettysburg.

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole (current post)

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.