Wells Waite Miller came from hardy English stock with his ancestors sailing across the Atlantic Ocean to immigrate to the American Colonies in the 1600s. Their names were Thomas Miller and Isabel (née Bird) Miller and, although they initially seemed to settle in well in their new homeland, they also created more than a whiff of scandal to add to the positive contributions they made.

English Ancestors of Wells Waite Miller

Thomas and Isabel were likely born in Bishop’s Stortford, Hertfordshire, England—Thomas on November 7, 1609 and Isabel in 1613. Thomas’s birth family, we know, was a fruitful one. His brothers included Leonard, Robert, William, Alexander, Jonathan, George, and Joseph—with sisters being Johanna, Grace, Anne, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Growing up in Hertfordshire meant being surrounded by a rich and storied history with remains existing from the New Stone Age and the Bronze Age and evidence of the Roman Empire so prevalent that it may have felt as though the empire had only recently collapsed. St Albans Cathedral, built in 793 CE, was a breathtaking site and so was Berkhamstead Castle, built in the eleventh century. Hertfordshire also served as home to one of the elaborate Eleanor Crosses built by King Edward I after the death of his beloved wife in 1290 to mark stops on her long funeral procession.

Migrating to the American Colonies

Yet, the couple left their life in England, immigrating to the American Colonies during the late 1630s—more specifically, to Rowley, Massachusetts. When they arrived, their new home surely looked untamed in contrast to the established life they had known in England.

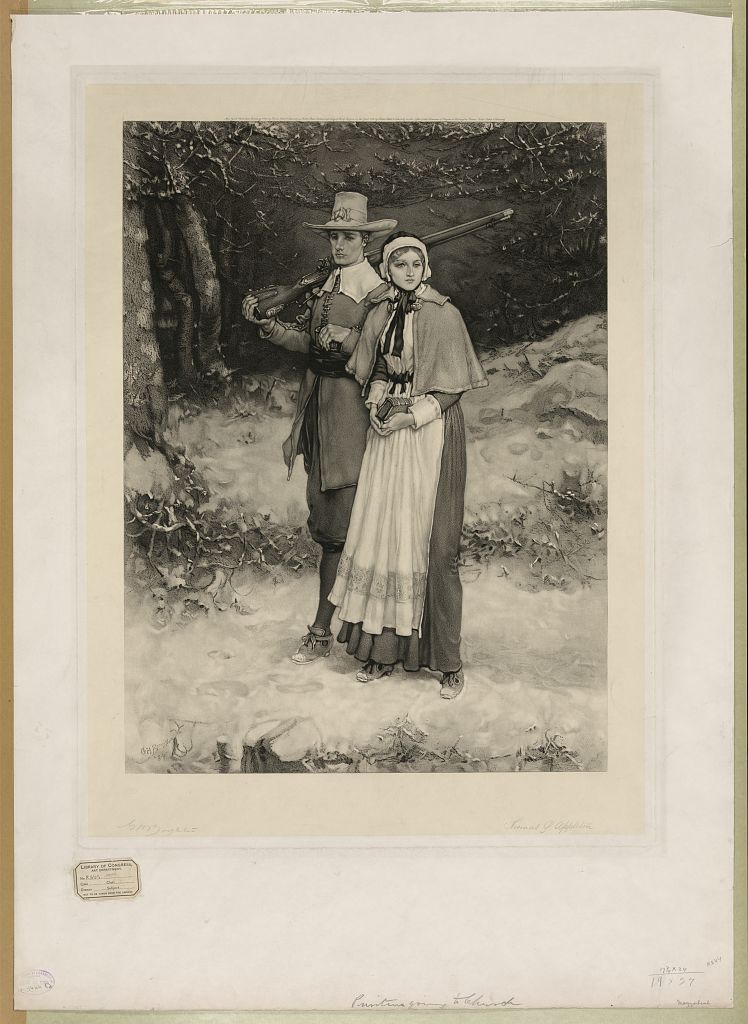

The couple would have come to the American Colonies as part of the Puritan Great Migration. In fact, as many as 21,000 Puritans may have left England for the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1630 and 1642 alone.

In England, Puritans were considered to be religious non-conformists because they believed that the Church of England (the Anglican Church) too closely resembled Catholicism. Puritans thought that the Church of England needed to be reformed—or “purified”—and, because the King of England was the head of the Anglican Church, this criticism was considered to be treasonous. In 1633, William Laud—the newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury—raised the stakes by taking harsher actions against people who held non-conformist views. This led to increasing numbers of Puritans fleeing to New England with the Miller’s hometown of Hertfordshire being one place where many fled from—right when Thomas, Isabel, and Ann did exactly that.

John of London

It’s possible that they sailed on the John of London that left England in 1638 although the Millers are not on any passenger lists that I’ve found. That ship contained a fiery preacher named Ezekiel Rogers who left Rowley, East Yorkshire in England with some of his parishioners. He named their new home in Massachusetts after the place they’d left and he also brought the first printing press to the Colonies. As another possibility, there is a ship that arrived in 1639, Jonathan, that shows a man named “Thomas Mills” on its passenger list.

Overall, Puritans left their homeland to escape religious persecution and to embrace a simpler way of worshipping God that they believed more closely aligned with Biblical principles. They saw themselves as God’s chosen people, men of destiny who were going to a modern day promised land. If you like in-depth history delivered with snark, then the video below is tailor-made for you (Well, heck. I see it’s no longer available).

Once the Puritans arrived in their new homeland, though, they quickly began establishing exclusionary policies of their own. In fact, in 1631—not that long before the Millers arrived—a Massachusetts law was passed stating that “no man should be admitted to freemanship but such as were members of some of the churches in Massachusetts.”

On September 3, 1635, it was determined that only freemen could “legally vote and hold office in town and province government.” So, when Thomas was declared to be a freeman in 1639, this is what gave him the ability to have a voice in their new community. He may have felt like this new homeland was the right choice for his family.

Rowley, Massachusetts

Rowley itself came into existence in 1639 and, as a book titled Early Settlers of Rowley, Massachusetts notes, “There is something fine and substantial in this planting. The building of homes in the wilderness, the setting up of town government, the founding of the public school, the organization of a church all point to a desire for an intelligent, upright, law-abiding community.”

By 1643, Thomas and Isabel had an acre and a half house lot; four years later—for the price of fifteen shillings annually—he was licensed to draw wine. He was also working as a carpenter.

For a quick overview of life in early Massachusetts, here’s a short video.

Middletown, Connecticut

In 1651 or 1652, the Miller family moved to Middletown, Connecticut. There, Thomas’s name was listed as one of the town’s original 23 settlers on the Founder’s Rock plaque placed at the Riverside Cemetery entrance. At a 1652 town meeting, he was named the Surveyor of Highways in a community that was, at the time, “just an outpost in the wilderness, a two-year-old settlement that was home to a handful of English Puritan immigrants and still known by its Native-American name, Mattabeseck.” Just like in Rowley, worshipping in the Puritan way, regular church attendance, and contributions to support the meetinghouse were mandatory.

Scandal in the Colonies

Although life was often brutal in this time and place, with people largely focusing on their survival and praying that they were one of the “Elect” who were predestined to go to heaven, all seemed to be going relatively well for the Millers—at least until 1666.

(If that sounds ominous, unfortunately, you’re correct.)

Wells Waite Miller: Exploration of His Life and Times

I’d like to share my research about Wells Waite Miller from Castalia, Ohio with you. Although I’ve written the material in the order in which I’ve found research material, I now roughly have the posts in the order in which the events occurred.

Blog posts I’ve written on the subject so far include:

- Wells Waite Miller’s America

- Thomas Miller: Ancestors in England

- Great Puritan Migration (current post)

- Scandal in the Colonies

- Calm in the Eye of the Storm

- Aaron Miller: Born Under the Drumbeats of War

- Grandparents, Parents, and Siblings

- Enfield, New York

- Ohio Bound

- Oberlin Years: Fierce Debates About Abolitionism

- Enlisting in the Civil War

- A Look at Lodowick G. Miller

- Captured: Camp Parole

- Marching Towards Gettysburg

- Picketts Charge and 43 Bonus Years

- Glory Days to Invalid Corps

- Castalia Massacre

- Calvin Caswell

- Calvin Caswell, Continued

- Obed Caswell And Walter Caswell: Story of Brothers

- Miller Family Mystery Solved?

- Miller Family Mystery Solved, Part Two

- Amos and Corinne Miller

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part One

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Two

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Three

- Oscar Schultz Kriebel, Part Four

- Erie County, Ohio for Congress

- Wells Waite Miller: Republic Candidate for Ohio Governor

- Ohio Antietam Battlefield Commission

- “Speaking the Names: A Tale of Two Brothers” at Ashland University’s Black Fork Review

I invite you to become part of this journey, sharing my posts with people who enjoy reading historical biographies.

If you read this material and have additional information that’s directly tied to Miller or sets context about his life—or you’ve spotted errors—please email me at kbsagert@aol.com.